This page describes the historical evolution of the automatic wristwatch with examples. For a more detailed explanation, I encourage you to read the section on the topic in Wristwatches: history of a century’s development by Kahlert et al.

The Harwood bumper watch

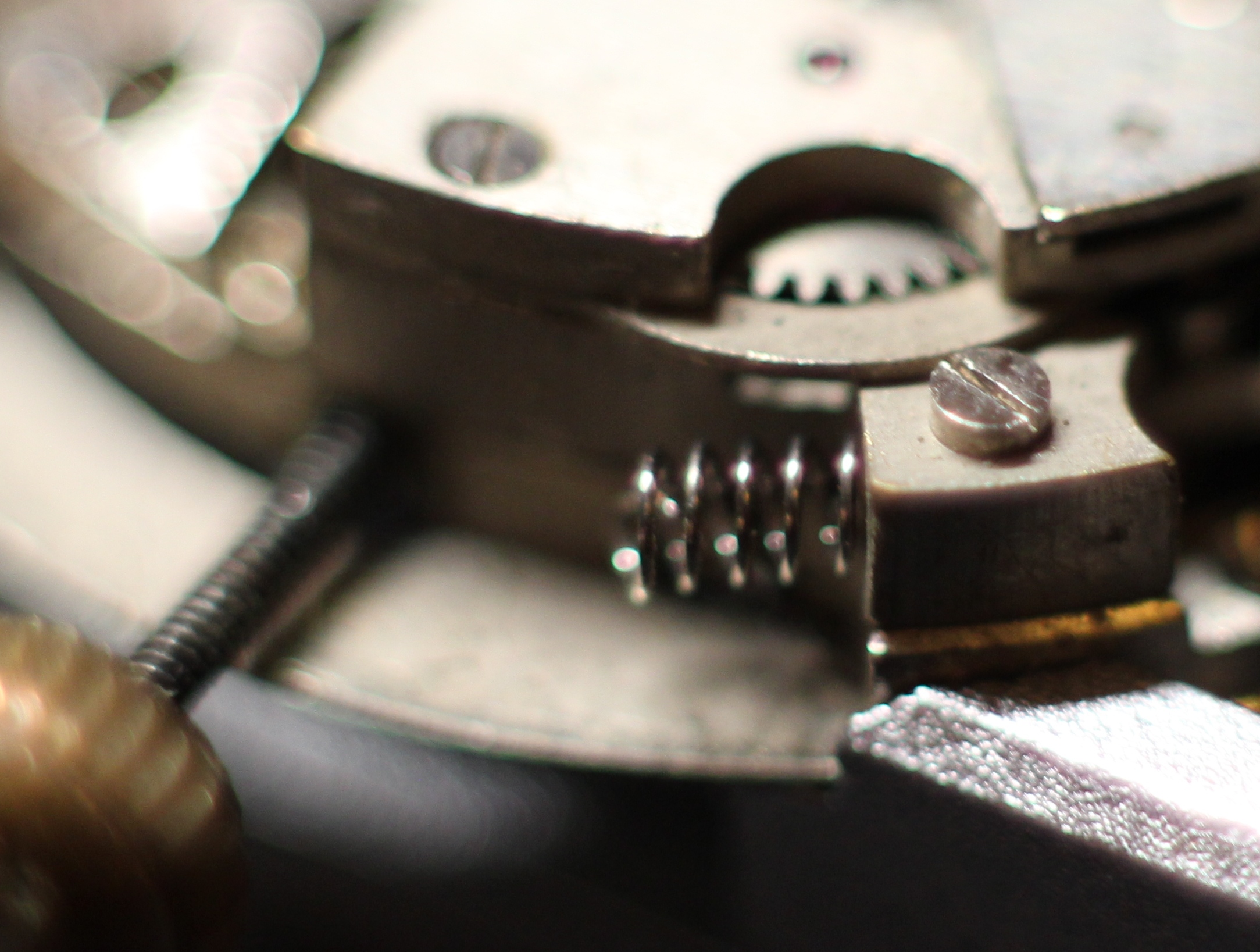

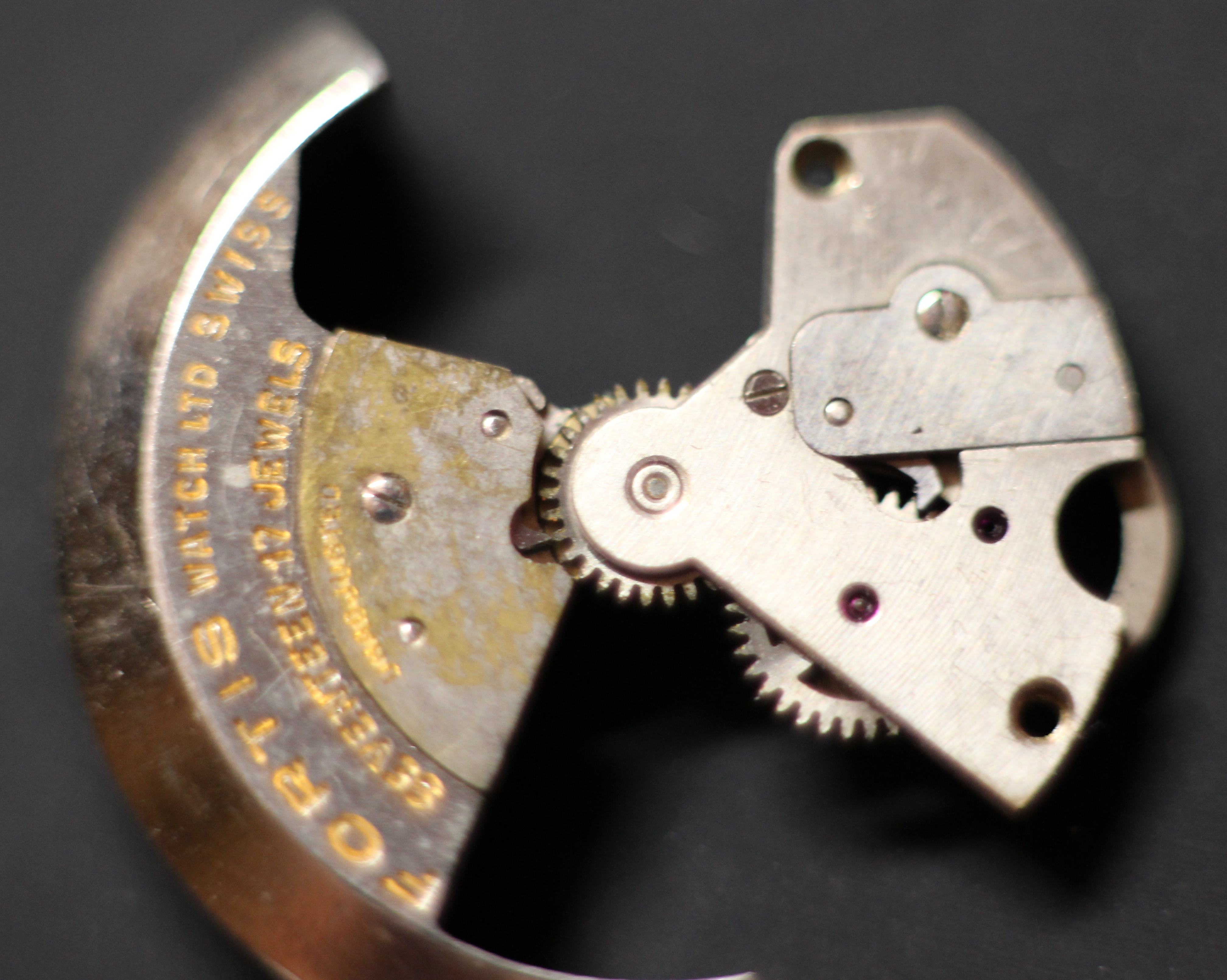

Designed in the 1920s by John Harwood and first produced commercially in 1928 by Fortis, the Harwood bumper system had a rotor that did not swing fully round the movement, but only about 200 degrees. At the end of its arc, there were springs (bumpers) designed to send it back. This system only wound the mainspring when rotating in one direction.

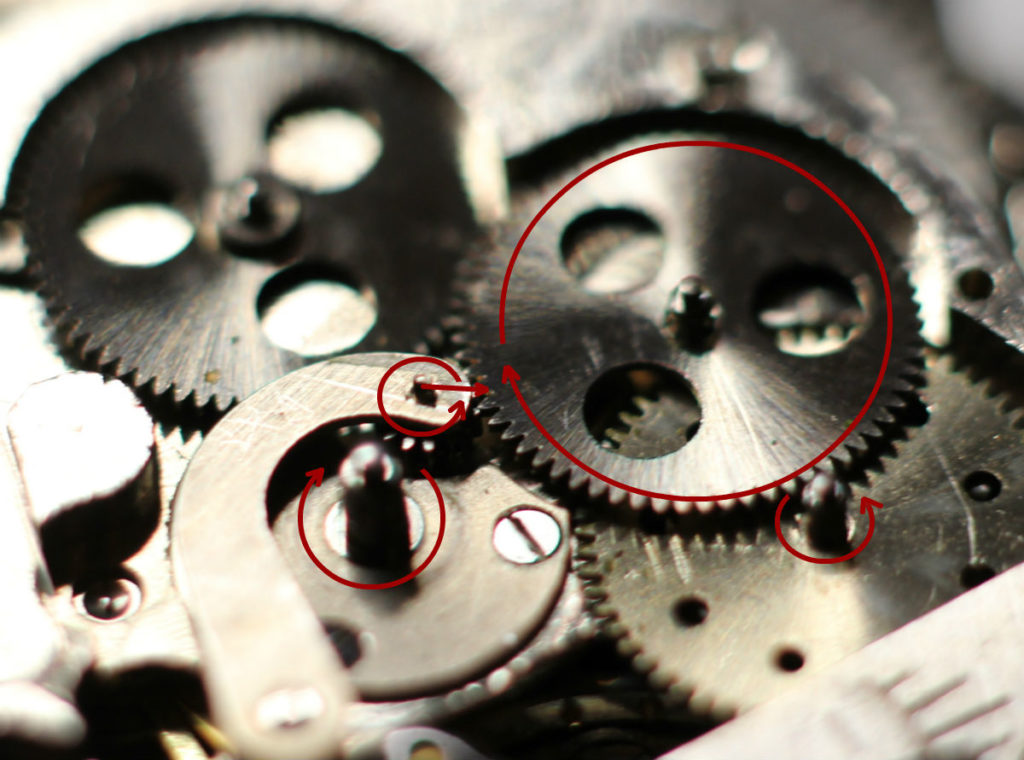

The pictures below are from an A. Schild 1250 movement in a Fortis watch.

Rolex perpetual

Rolex improved the Harwood system by getting rid of the bumpers and having a rotating mass that could rotate 360 degrees, avoiding the jerking sensation linked to the rotor hitting the springs.

Felsa Bidynator

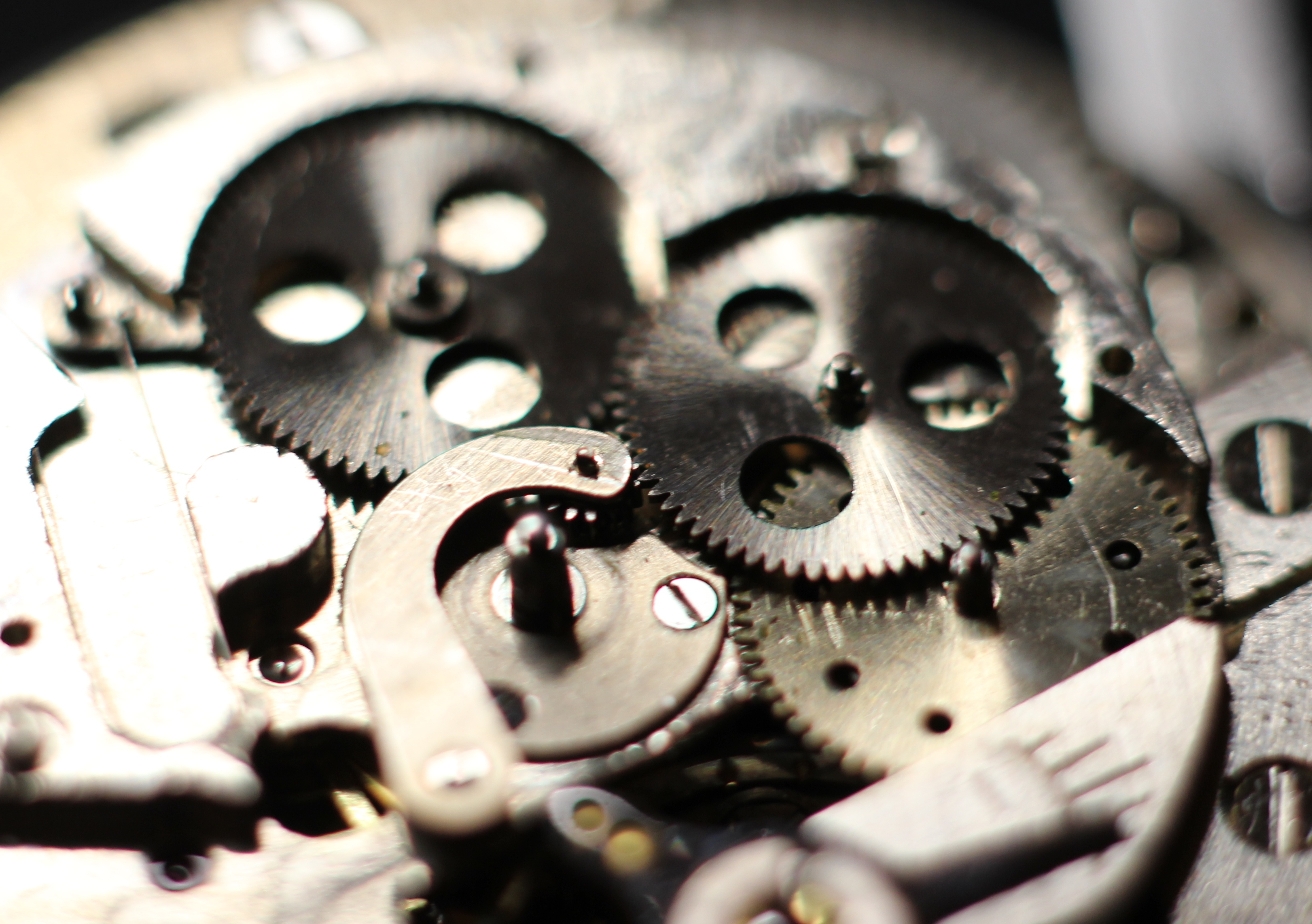

The Bidynator was one of the first movements to introduce bi-directional winding. The rotor is now above the automatic mechanism and can rotate 360 degrees. A rocker linked to two reverser wheels ensures that the mainspring barrel gets wound whatever the direction of the rotor.

Eterna ball bearings

In 1948, Eterna introduced ball bearings to reduce friction around the rotor pivot and improve durability.

Micro-rotor

Buren collaborated with Hamilton on one of the first movements with micro-rotor. It made possible automatic watches that were extremely thin, less than 3mm in the example below. To achieve this, the centre wheel is moved to the side and drives, through a hole in the base plate, a friction wheel attached to the cannon pinion. The automatic mechanism, instead of being on top of the movement, is integrated on the opposite side as the gear train.

Peripheral rotor

The peripheral rotor was patented in 1955 by an independent watchmaker and produced in the 1970s and 1980s by Patek Philippe (Cal. 350). However, the system did not work well.

Citizen used a partly peripheral movement in its Super Jet watches. Although the rotor was not centrally attached, it was not completely at the periphery of the movement either.

In 2008, Bucherer developed a functioning version and several other brands have followed suit as the advantage of this system is to make the whole movement visible without adding to its thickness.

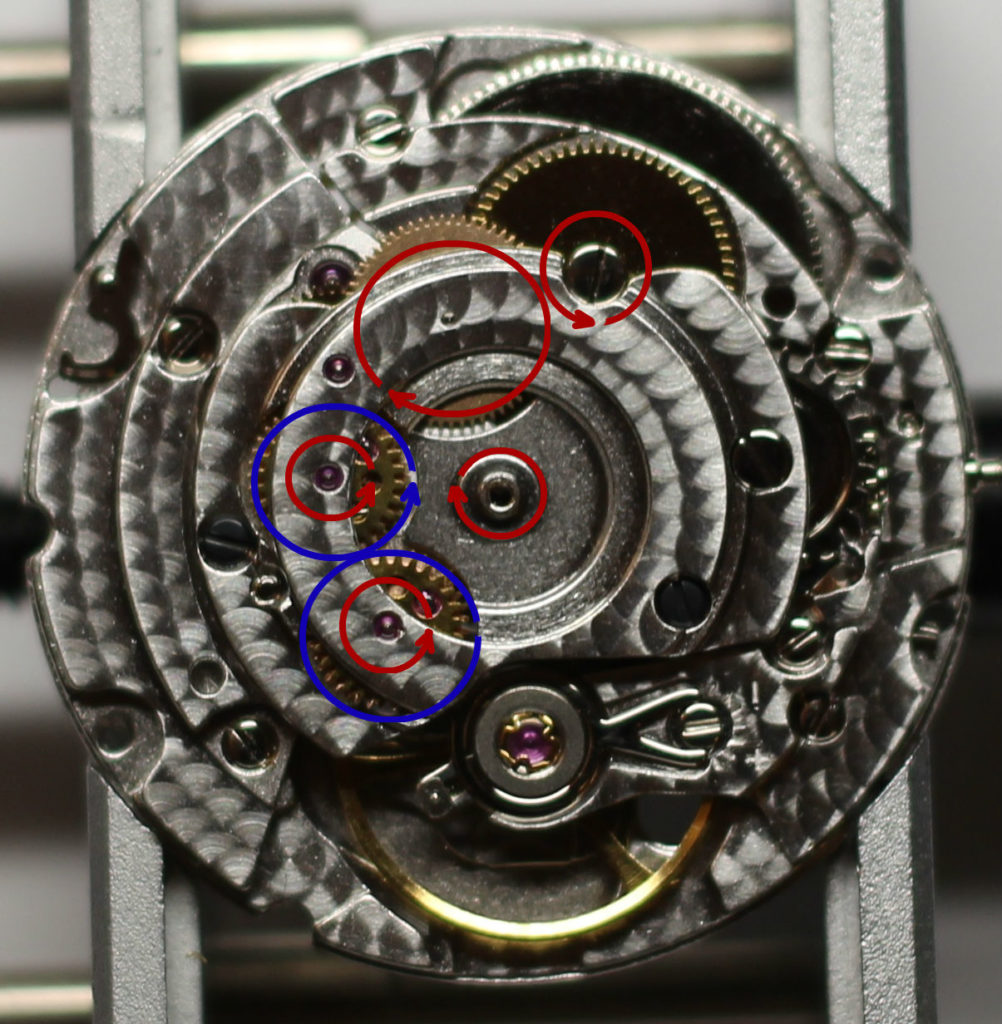

Reverser wheels

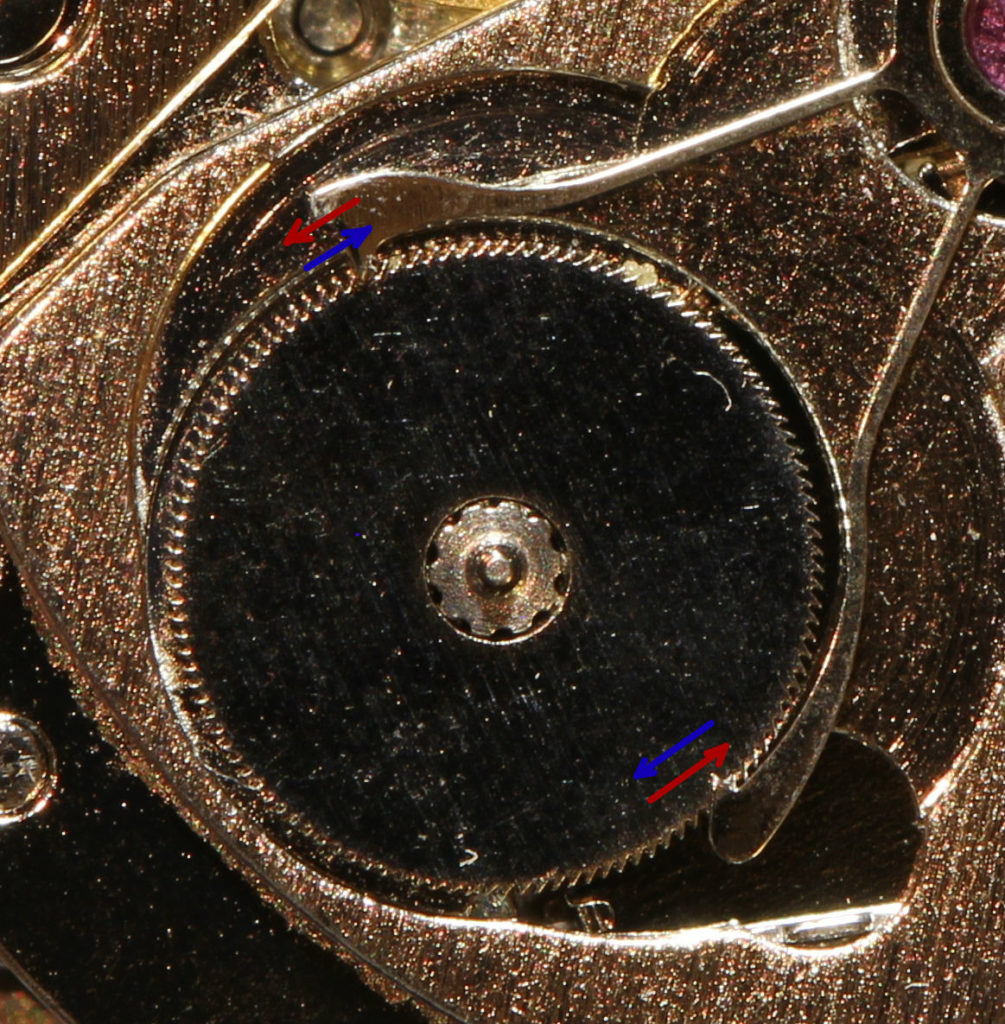

Reverser wheels are the most common type of system ensuring bi-directional winding nowadays. They are two double-wheels connected to each other. On each double-wheel, the top wheel will only drive the bottom wheel in one direction and will simply slip over it in the other. The pictures below show the direction of rotation of each wheel for each direction of the rotor. The example is a clone of the ETA 2824. The reverser wheels are those with both a blue and a red arrow. The red arrow shows the rotation of the top wheel and the blue arrow shows the rotation of the bottom wheel. Please note that I don’t know which way the ratchet wheel is supposed to turn, so maybe all arrows should be in the opposite directions, but this does not affect the explanation of the system.

- If you want a more detailed explanation, you might like the short article by Walt Odets in Timezone.

Sliding or switching-rocker system

Another type of system involves one or two small wheels able to slide or rock on a platform depending on the direction of rotation of the rotor and gearing with either one of two wheels.

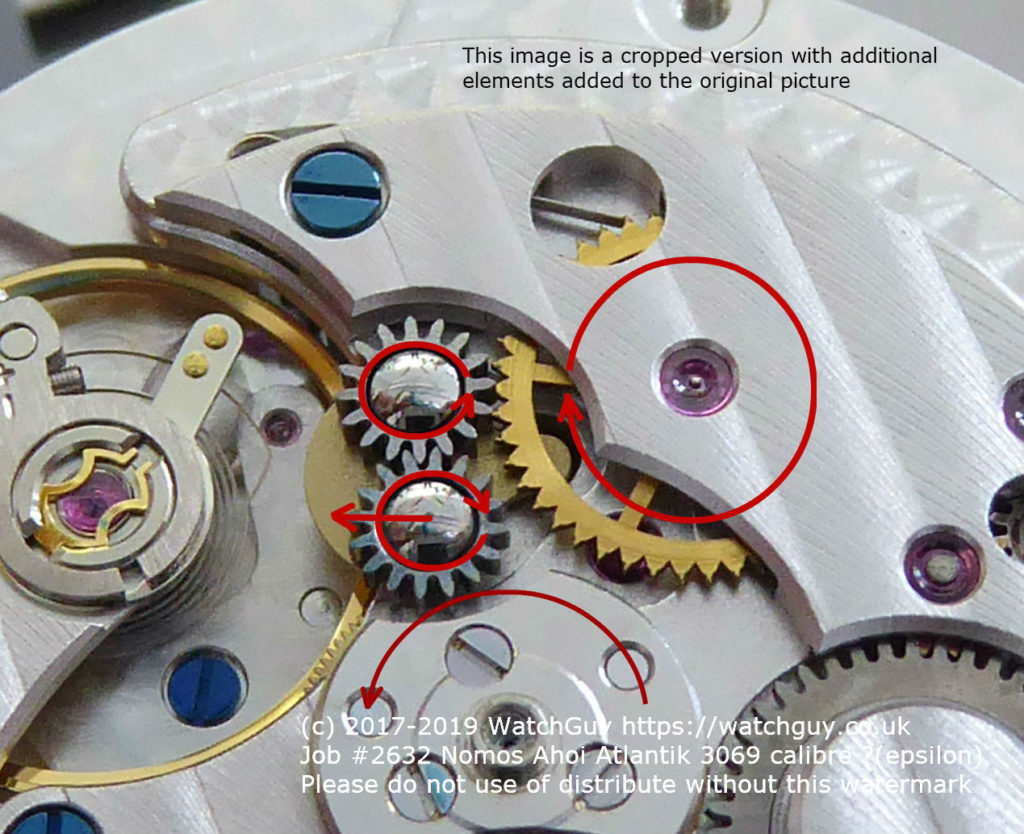

The first example below from the Felsa Bydinator shows a small wheel mounted on the end of an arm that can move so that the small wheel makes contact with either one of two wheels.

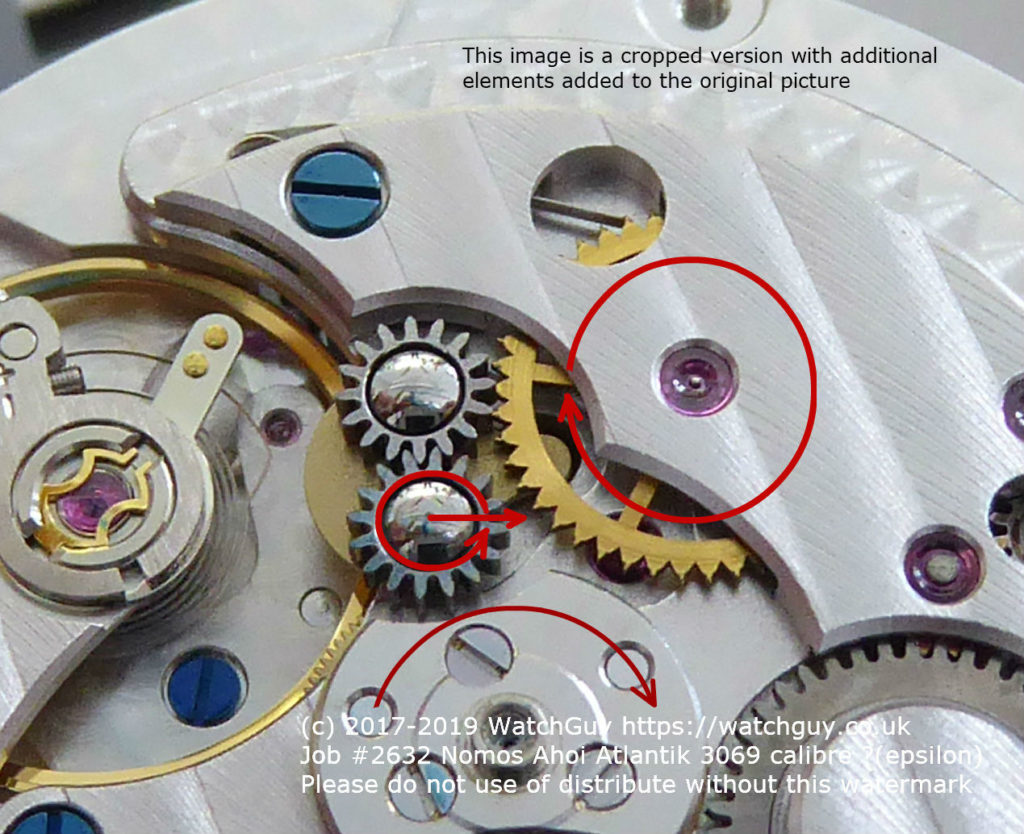

Similar to this system is a system of two small wheels mounted on a switching-rocker platform. The difference is that you have 2 small wheels moving to make contact with a single larger wheel instead of one small wheel making contact with either of 2 larger wheels. I must say I find this system very elegant, both intellectually and visually.

The example below is from a Nomos Epsilon, but I have read somewhere the system was originally designed by Jaeger-Lecoultre. Please note the original pictures that were modified were from the Watch Guy’s website.

Seiko’s magic lever

I have a skeletonized watch with a Seagull ST16 movement and I was interested by the automatic system that does not have reverser or reduction wheels, leaving the movement visible in the skeleton version. According to information found on the Caliber Corner page, this system is known as the magic lever and was developed by Seiko. It can be seen in the Seiko 7005 I disassembled.

The system works thanks to an excentric pin being rotated by the rotor. That movement of the pin moves the arms of the lever to either pull or push the ratchet wheel. Because of the shape of the ratchet wheel teeth, the lever arm moving to unwind the ratchet wheel will simply slip over the teeth.