- ETA’s page for the movement has all the technical details

- ETA’s training tool has a step by step guide to disassembling the movement

- Horlogerie Suisse has a page in French dedicated to the movement

- The Watch Guy has documented the service of several 7750s in Vixa, Breitling and Omega watches

- The Naked Watchmaker has also deconstructed a 7750 from a Breitling Navitimer

Main technical specifications (from Watchbase)

- Movement: Automatic

- Diameter: 30mm

- Jewels: 25

- Power reserve: 42 hours

- Frequency: 28,800 bph (4Hz)

- Complications: Time (incl. small seconds), Date, Day, Chronograph

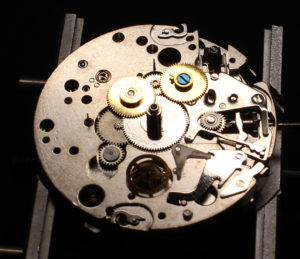

The movement below is a clone of the ETA 7750. I disassembled it following the instructions of Eta’s Swisslab online tool. As far as I can tell, the Chinese did not bother to give it a name and it is referred to on forums as the Asian 7750.

Before disassembling this movement I wondered why it took several decades to produce the first automatic chronograph once both the chronograph and automatic technologies were available. I better understand the challenge now.

The 7750 is a workhorse, but not a beautifully designed movement. The base movement is sandwiched between the chronograph module and the calendar module. The chronograph hour recorder and hammer are on the dial side, so the chronograph function is divided.

I must confess I came to this movement with a bias as I don’t see the point of the week day indicator or of the chronograph hour recorder (I’ll admit I’m not a long distance runner) that just clutter the dial. I also prefer column wheel chronographs that I find more elegant.

The keyless works have 3 positions: wind, change the date and day, and set the time. This is achieved with a sliding pinion (the one with 5 fingers) that connects with either the date or the day disk depending on the direction the crown is turned in the middle position. I like this solution and I don’t understand why ETA don’t use it as a reverser solution in their automatic system (see the Nomos Epsilon).

The large pinion towards 8 o’clock drives all the non-chronograph wheels and is driven by the main wheel of the base movement.

The rotor is providing the energy to wind the main spring. There power must therefore be transmitted from the rotor to the base movement through the chronograph layer.

The automatic system is competing for space with the chronograph module, which is probably why the hour recorder is on the dial side. The automatic system is placed where the operating cam is located on most manual wound chronographs.

On the left of the chronograph seconds wheel, at the end of a lever, there is the small pinion providing power from the base movement.

On the picture below, the pinion transmitting power to the chronograph module has been removed, but its position is visible on the right side of the fourth wheel.